- Dun in Mara's Newsletter

- Posts

- 'Tis Dun in Mara - October'25

'Tis Dun in Mara - October'25

Your chronicler reports on the shire's tidings and tales

Targets cannot duck, but we sure can!

What do time and arrows have in common? They both fly when you’re having fun. And fly they absolutely did at Duck Too!, the second of its kind.

On the 30th of August, which already seems a lifetime ago, many of our members throughout the land gathered in Clara to string their bows, aim their arrows, shoot at their quarry (not ducks), and eat the wonderful food provided by our cooks (mostly not duck). Our Marshal in Charge Lady Gabriella della Luna provided guidance and wisdom, helped by THL Alays de Lunel, Noble Ingemar and Baron Robert in keeping the scores tracked, the time checked and the ducks in a row. The first challenge which had the participants quacking in their boots was the Portsmouth (10 rounds of 6 arrows) on a stationary target at 20 yards (which is definitely within duck egg throwing distance given that the current record is set at 71 meters, held by two Irishmen at the Irish National Open, though that was for hen’s eggs, admittedly).

Alas, with the duck being a waterfowl, a day of pure blue skies would have been unseasonable and so the conditions became decidedly more wet throughout the competition. Though the archers did not let that ruffle their feathers, they wisely took shelter when the rain got too heavy and opted to continue the competition after lunch.

Counting is serious business, especially when the Baron is involved. |  Arrows in the air, ready to fly. |  Ducking from the rain or ducking from the arrows? A&S is safe inside. |

While the archers outside were honing their skills in bringing in the food, our wonderful cooks led by Máistir Aodh Ó Siadhail actually brought food, nay, a feast to the table. In the words of the master himself:

Duck Too! was a one-day event, with the main meal served at lunchtime. The original idea was to do a duck dish, but it turns out that duck is hideously expensive, so I ended up doing a chicken dish instead: Chicken Baked with Prunes, from Magdalena Thomas' translation of Food and Drink in Medieval Poland: Rediscovering a Cuisine of the Past by Maria Dembinska. It's an excellent book, although I want to dig into the recipes a bit more; the originals aren't given, and there are often a lot of ingredients. I tried the dish at a Dun in Mara Arts & Sciences Day, and it came out well, so I was pretty confident of it going down well.

I did a few side dishes to cater for allergies, and served rice alongside, which seems to be more-or-less appropriate for the period. I'm going to have to work on the rice, though, because it came out a lot stodgier and stickier than I liked, and cooled off rather faster than I expected too. Large pots of water are something of a weak point in many of the kitchens we use; it's hard to know when they'll come to the boil, and even harder to know when they'll come back to the boil having had food put in them.

I did serve some smoked duck alongside, which I could get hold of at semi-reasonable prices, though it had to be sliced thinly. And then I did a Court Dish of Baked Fruit, from the same book, as a dessert. I'd done this before for an Arts & Sciences Day in 2024, and it went down very well. It's vaguely like a crumble or an Eve's Pudding, but uses a sort of porridge made with butter, breadcrumbs, milk and eggs in place of the dough.

The reduced effort of cooking a main meal that isn't really a feast at lunchtime is an interesting approach, and I think I'll probably continue to do it for one-day events. Quite apart from anything else, it allowed me to go and nap by the fire for the afternoon.

Viscountess Agnes helping to prepare lunch |  Pre-lunch shenanigans. The anticipation was strong. |  Lunch being inhaled. Rightfully so. |

The Portsmouth was at last completed in the afternoon (thank the weather gods) and swiftly followed up by the field shoot. It came under a bit of a time crunch but several archers bravely followed our marshals into the woods. Legend has it none got lost and every single one of them made it back in time for court.

Before we move on to an account of court, let us take a moment to appreciate the archers and the winners of both competitions. The Portsmouth’s highest score was reached by Joszko with an amazing 231 points in total, and the field shoot saw two contestants of equal skill, with both Joszko and Stanilav each having secured 20 points. Congratulations to the winners!

Official Business at the Court

With both Prince Etienne (from the line) and Princess Susanna (from a safe distance) overseeing the shooting (no arrows were shot in Their direction; we have nothing but admiration and love for our Highnesses), the archers made sure to display their skills to their full extent.

Having been appeased by both the prowess and the food, our Celestial Highnesses held court and awarded two esteemed members of the populace with the order of the Fox (your humble author feels there is a potential jest in there, awarding Foxes at an event called Duck, but was unable to bring it to fruition).

Lady Gabriella della Luna was awarded the Order of the Fox with a scroll by Mistress Órlaith Ildánach

Lady Gwerful an Filí was also awarded Order of the Fox with a scroll by THL Alays de Lunel, and with words by Máistir Aodh Ó Siadhail.

A glance of the future

As we look back fondly on the days of Duck Too! or Autumn Crown, let us cast our gaze to the future and see what awaits us!

As we are nearing the colder and therefore more indoor season (at least, your humble author does not enjoy the cold and would prefer to be wrapped in several blankets for most of it), it is time for us to turn our attention to A&S! We have several upcoming A&S meetings scheduled in Santry, and all are welcome to join. Please see the events page on our website for the links to buy tickets.

While thine eyes glide over the upcoming A&S days, they might spot a new event on the calendar: namely Imbolc. It is set to take place on the 1st of February 2026, so it’s something to look forward to as we harvest the last of the apples, see trees lose their leaves and endure the increasingly nippier weather.

With Imbolc centered around food preservation, now is an excellent time to start thinking about how you could preserve food for consumption in several months time, for that is our intent! At Imbolc, all of us will contribute towards feast by bringing in dishes made with preserved food, in whichever way of preservation possible, such as conserves, pickles, dried fruits or legumes, and many more.

For those of you who wish to attend an event on this island before the turn of the year, this humble author would encourage you to peruse the calendar of our cousins in the West, for they may have something to tickle your fancy. What say you of some ghostly business at Medieval Dead?

Autumn Sonnet 2024

composed by Máistir Aodh Ó Siadhail

Sharing with us a sonnet of his own:

My harvest is more words and deeds than grains,

My crops more thoughts than leaves and solid roots,

Others’ regard a measure of my gains,

A harvest grown from springtime’s solemn moots

But harvest reaped brings earthen joy to winter,

Provides the food that through the cold sustains;

As days go dim, what’s brought becomes the centre

And in the frost the fallow field remains.

As summer’s light from bounty now pours forth,

The summer’s labours, gentler, warm us more

Than planting, gleaning, reaping did, to sort

Into the dark well-armed, warmed to the core.

But how the mind will not lie still, wanting

To go past the snow, to next year’s planting.

Máistir Aodh explains on the form: The sonnet is the most Shakespearean of poems; almost all the poetry William Shakespeare wrote was in this form, and there were plenty of other writers in the late 1500s using it (Spenser, Sidney, Howard, Constable, etc.). Indeed, what’s sometimes called the English Sonnet - to differentiate it from the Italian or Petrarchan sonnet - we frequently know as the Shakespearean Sonnet.

The English sonnet has the usual 14 lines in iambic pentameter (off-on stresses, repeated five times for a total of ten syllables), arranged in three quartets (four lines each) and a couplet at the end. The rhyme scheme is ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. In the Italian sonnets, it’s usual for the volta (“turn”) to occur at the 8 line mark - this is where the poem changes direction, presenting a different point of view in the final 6 lines. In the English sonnet, the volta happens more often at the 12-line mark, making the final couplet the differing point of view. In Shakespeare’s poetry, this sometimes makes it almost like a punchline to a joke.

The Autumn Sonnet fits this form exactly, with the turn from consideration of the metaphorical harvest to next year’s planting after 12 lines.

Arts & Sciences, illuminated

created by Lady Erin Volya

As many of you are already aware, Drachenwald gained a new member of the Order of the Mark at this year’s Autumn Crown over on the Big Island. This joyous occasion of course also called for the creation of the regalia, a pair of white bracers. The honour befell one of our own, Lady Erin Volya who is often seen making or carrying leather items of her own making. She produced a wonderful pair of bracers:

Master Yannick donning his new bracers - Photo by Duchess Angharad Banadaspus Drakenhefd |  The bracers - Photo by Lady Erin |

In the words of the creator: These braces are each carved from single pieces of leather including their straps, then glued to dyed white calfskin on the inside for comfort. The carving was inspired by the Anglo-Norman architecture of Llandaff Cathedral in Wales, in honour of Master Yannick's persona, with his heraldry and the symbol of the Order on the doors; with his noble heart and kind nature does he open the door to all comers to the Known World old and new. White acrylic was layered through countless applications of water-thinned paint. Weathering was done with dark brown antique that washed the colour into cream. As a personal touch, the Drachenwald heraldry features a more serpentine, East Asian dragon.

The words are a modified passage (805) from the Song of Roland, an 11th century chanson de geste, as follows:

Left bracer: Nous te donnons l'arc que nous avons

Right bracer: tendu a te trouver tres bien li alut

In English: "We (the royals) hand you this, the bow we have drawn / our bow, in order to aid you."

Translation and modification by Master Ari Mala and calligraphy provided by Master Melisende.

Details of the arch - Photo by Lady Erin |

Today, but several hundred years ago!

Have you ever wondered what happened on the 19th of October, but in the year 1216? No need to look further (but if you want to, please do), your humble author has done some research for you.

19 October, 1216: King John of England dies and is succeeded by Henry III, his nine-year-old son.

King John reigned in England from 1199 to his death in 1216, and lived through some interesting times, including the collapse of the Angevin Empire, a papal excommunication, the signing of the Magna Carta and the first Baron’s revolt when the Magna Carta was annulled. He does not seem to be remembered fondly by history, and has been given some less favourable nicknames, such as “John Lackland” and “John Softsword.” It makes sense then that some of us might also recognise him as the inspiration for a certain lion-shaped character in an animated movie, where he still bears the title of prince as his older brother King Richard II, also known as Richard Lionheart, was still reigning in that setting.

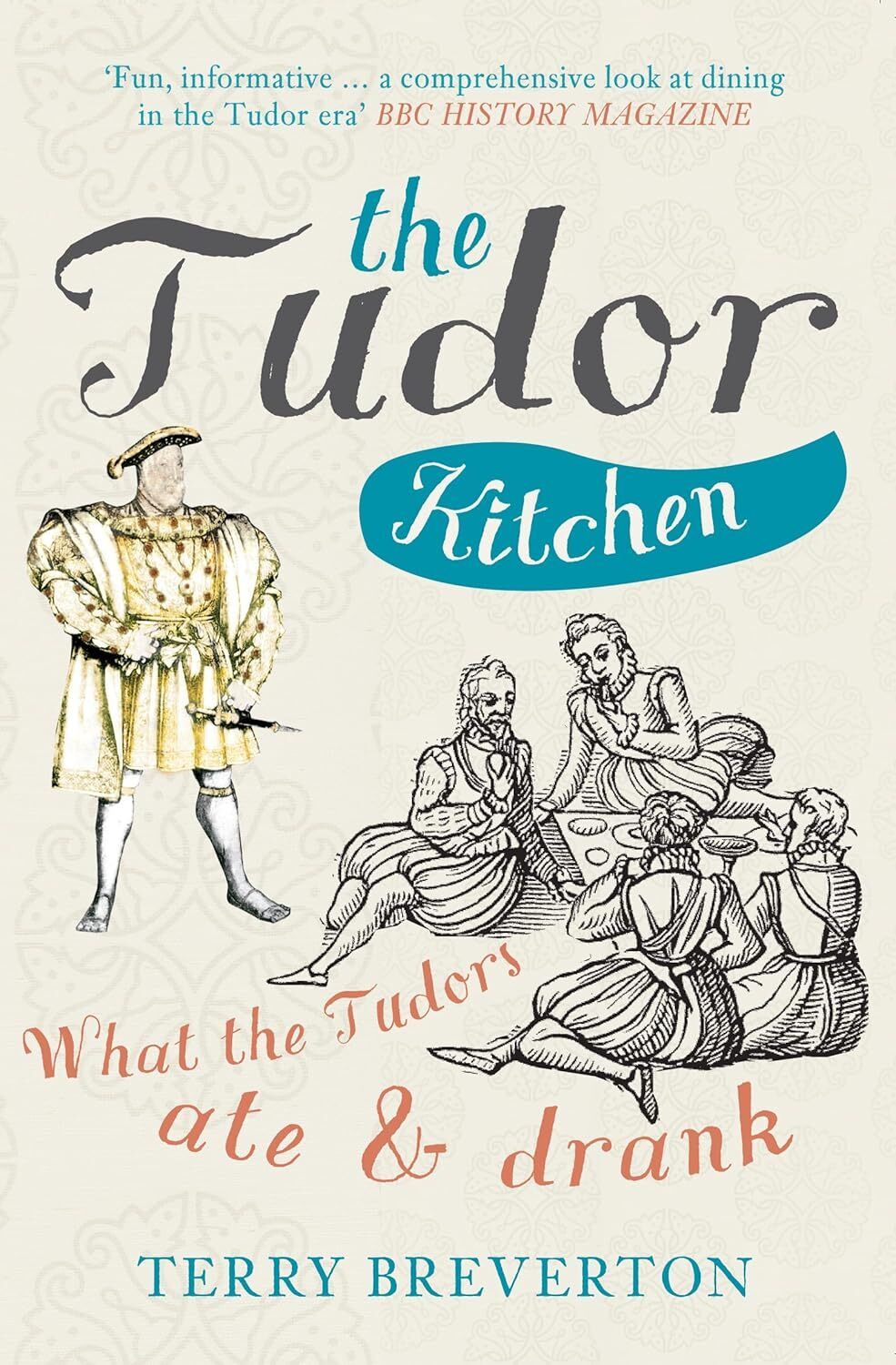

Book review: Tudor Kitchen

| Published: 2017 Publisher: Amberley Format: Paperback, 352 pg ISBN: 9781445660400 Language: English |

The scores:

Outlandish recipes: 7/10 organised in a separate chapter, they definitely make for good reading, if not per se tempting.

Sweet tooth satisfaction: 8/10: the chapter on sweets is by far the longest in the book (60-ish pages).

Fun facts: 7/10 old-fashioned names for measuring units are fascinating, and this author delighted in finding out that the Portuguese word for barrel (pipa) actually also translates into English as pipe even though the volume is not the same. A pipe is not a small measurement, unlike what the name might suggest.

Pictures and/or illustrations: 6/10 there are a few pages of illustrations and photos of a Tudor kitchen and while they are interesting, this is mostly a text-based book.

The contents:

Upon first inspection, the book seems really well organised into two parts with thematic chapters. Part 1 contains the necessary literature to provide context to the Tudor Diet, while Part 2 contains primarily recipes used at the time.

Part 1 (The Tudor Diet) contains chapters on Tudor farming, Tudor food, Tudor drink, the Tudor kitchens at Hampton Court, and lastly a chapter on Tudor table etiquette, banquets, sumptuary laws, and interestingly the waist of Henry VIII.

Part 2 on the other hand is filled with recipes, and like with many recipe books nowadays, the recipes are divided into courses or purposes, which seems part of the author’s efforts to make the content more approachable from a modern reader’s perspective. There are chapters on first courses, main courses, side dishes, sweets, snacks, drinks, preserves spices and sauces, and lastly the more questionable “dishes you may not wish to cook (or eat) (or see)”. This author is inclined to agree with the assessment of the author of The Tudor Kitchen in that some of those recipes will likely not make it to the dinner table in many households nowadays. One of the more well-known “grotesque” recipes in this chapter is the cockatrice, of course. The chapter also has a recipe for haggis and instructions on how to prepare animals or parts of animals that we are no longer used to eating nowadays, such as cow’s udders. The author also wisely advises against following the instructions for preparing swans, and recommends to use geese instead.

The recipes have been adapted in different ways. Some recipes are printed directly as they are in the source material while others have a “translation” to modern English cooking methods, and sometimes the recipes have both. The famously not-Tudor blender make an occasional appearance, for example in White Gelly of Almonds (p. 230, Sweets) and Leach ( p. 208, Sweets), which is an Elizabethan almond panna cotta. One could argue that the modern oven the author uses also wasn’t available in that era, so we shall interpret these instructions as for The Modern Eye. The author also admits to providing a guesstimate for some of the recipes as quantities were not always present in the source material, and thus manages to make the recipes more accessible to those not well-versed (yet) in the art of medieval and Tudor cooking. (As a true beginner in this respect, this author quite definitely appreciates it.)

What this author particularly enjoys is silly recipe names. There is a number of them throughout but here are some that this author found amusing:

A Dish of Particular Colours (p. 116, Main Courses),

Starrey Gazey Pie (p.152, Main Courses),

Sprouts of Life (p.166, Side Dishes),

Compost (p. 165, Side Dishes),

Egges in Moneshyne (p.195, Sweets),

A Dysschefull of Snowe (p.203, Sweets), and

Lamb’s Wool (p.328, Drinks)

The over 500 recipes are pulled from a variety of sources, including some well-known books such as The Forme of Cury, and the book claims to only include recipes that would have been consumed during the Tudor era (1485-1603). The evidence for this is presented in the last chapter of the book: the sources. This section is very interesting for those of us starting to explore the arts of medieval/Tudor cookery, because not only does it list the titles and publication years, there is often a little extra information on the source. Additionally this chapter contains a list of interesting secondary sources, and some useful websites.

With the aforementioned 500+ recipes, one might have expected there to be an index of sorts. Alas, ‘tis not the case, and so we must rely on a good memory or (more likely) good bookmarks. The categorisation of the book does allow us to locate the right section, and the recipes are somewhat grouped, for example the various fritters are listed together despite their various names, e.g. Fruturs of Fygis, Samacays, Spynoche Frutures and Tourteletes in Fryture (p. 260-261, snacks). However, if you wish to make Mistress Sarah Longe’s Sugar Cakes (p. 249), you will have to remember that it is considered a snack and not a sweet in this book. The same might occur with various other recipes, for example My Lady of Portlandas Mince Pyes (p. 87), which could easily be considered a snack or a side dish, but is in fact in the first course chapter.

Overall, this author is quite pleased with the book and has a lot of recipes to explore. Perhaps the results will even make an appearance at a future event, but no promises to that end shall be made.

Did you enjoy this read? Consider submitting content for the next edition!

Please contact [email protected] for questions, feedback and content submissions. We welcome any ideas or suggestions 🙂

If you received this email but aren’t subscribed yet, click here to make sure you get the next edition!

Cover photo by Lord Daniel.