- Dun in Mara's Newsletter

- Posts

- 'Tis Dun in Mara - July'25

'Tis Dun in Mara - July'25

Your chronicler reports on the shire's tidings and tales

Strawberries were raided: a phenomenal event

One could say that Strawberry Raid has in recent years grown to be the crowning event of Dun in Mara, and this year one could take that literally: Strawberry Raid IV played host to the Insulae Draconis coronet tournament. Our (pre-tournament) Celestial Highnesses, now known as Viscount Alexander of Derlington and Viscountess Agnes de Boncour, had served our wonderful principality for 9 hopefully short months, and saw fit to pass the baton coronet in Sigginstown. Travelers from over the hills and far far away made their way to the castle grounds, pitched their tents and gathered to watch not only the thrilling tournament, but also to enjoy the classes, compete in archery competitions, take in the views of the castle and its surroundings, participate in the island’s first Laurel Prize Display, and to catch up with old and new friends around the campfire.

A friendly (?) game of chess between Baron Etienne and Magnifica Marcella - photo by Master Agnes

The Arts & Sciences were certainly practiced this event. With 22 classes on subjects such as weaving, shoe making, hedgebothering, silver forging, natural dying, bardic, and cheese, there was surely something to everyone’s liking. (This humble author attended much fewer classes than she would have liked, but one cannot split oneself in two, not even for cheese.) It must be called out that many classes were taught by those not from our shores and so we had the opportunity to benefit from knowledge not usually available to us here in Dun in Mara. Contessa Saxa delighted us with no less than three classes (Weave Språng Garters, Intro to the Chiton, and Intro to Hand Felting). Other wonderful teachers included Roibeard mac Neill, who actually brought an anvil for his silversmithing class, Baron Eduard Tuve who talked us through the process of making 14th century turn shoes, and many more.

Hedgebothering - photo by Master Agnes |  Muinteoir Robert demonstrating silver forging |  Noble Ingemar explaining how to use a spindle for spinning |

While we had many visiting teachers, the event also saw some local teachers spreading their enthusiasm for their craft, such as Lady Gertie Hoode who taught a class on hand sewing, Noble Ingemar of Dun in Mara who taught a class on spindle spinning, and Noble Mallymkun who taught a class on fingerloop braiding. An honourable mention to Lady Gertie and Mistress Órlaith who joined forces and taught a class spread over four days on natural dying with fantastic results:

Mistress Órlaith and Lady Gertie, dying the medieval rainbow - photo by Lady Aoife

Coronet tournament was, as to be expected, a wonderful thing to see. The contestants were introduced with the most splendid and amusing boasts (which are published in the Baelfyr, and this author recommends having a read) while wearing their finest to appear in front of Their Celestial Highnesses. Much wisdom was bestowed upon both fighter and consort before the tournament commenced. Much chivalry and proficiency in the martial art was observed, together with quite a few hits that may have had the consorts fret just a tiny bit over the well-being of their fighters. However, all ended well and all fighters made it to court alive, if perhaps somewhat worse for wear.

THL Mícheál and Lady Gwerful during their boast - photo by Lady Gertrude |  THL Mícheál versus Lord Etienne the Younger, with consorts Susana and Gwerful watching. |  Fighters, consorts & heralds, waiting to present themselves at court - photo by Lady Gertrude |

Having defeated his opponents, Lord Etienne the Younger won the Tournament and was crowned the new Prince of Insulae Draconis, along with his consort Lady Susannah of York, now Princess of Insulae Draconis. Vivant!

Photo by Lady Erin

Official Business at the Strawberry Court

While Their (former) Celestial Highnesses Princess Agnes and Prince Alexander had much to do during the event, they dedicated their penultimate court, in part, to honour several members of Insulae Draconis. In no particular order:

Lord Anthony de Ponte Fracto received his AoA, accompanied by a scroll made by THL Alays de Lunel, and words by Máistir Aodh Ó Siadhail.

Lady Saskia de Quaasteniet also received her AoA, with a scroll by Lady Kytte of the Lake

Lady Haesel de Berneslai was awarded the Order of the Sun and Chalice, and received a scroll by Mistress Órlaith Ildánach.

After the tournament the coronet had passed along to a new set of heads, and so reigning Celestial Highnesses awarded Master Agnes and Lord Alexander with a viscounty.

Photo by Lady Erin

As part of their first court, the Prince and Princess invited members to their retinue, including the infamous Eplaheimr Brute Squad, and found a court jester in Lord Anthony, who shall hopefully bring much merriment and laughter during his time in the celestial court.

Let us end this section with a massive thank you to the event team and all who contributed to make this event a success!

A glance of the future

As we look back fondly on the days of Strawberry Raid, let us cast our gaze to the future and see what awaits us!

The next event organised by Dun in Mara is Duck Too!, the follow up of last year’s Duck! A fun day of throwing sticks at targets. With Lady Aoife ní Aodhagain as the event steward, Lady Gabriella della Luna as our marshal-in-charge and Máistir Aodh Ó Siadhail as the event’s cook, we are sure to have another fun day of throwing sticks at targets!

Activities planned for Duck Too! include, as one might expect, archery! Both target practice and a field shoot have already been scheduled. For those who are okay with not whacking sticks at a target, there will be plenty of space to engage in the Arts & Sciences, and they are encouraged to come along for the food and the fireplace.

Booking is essential, so get your ducks in a row and make sure you don’t miss out by getting your tickets here.

No Summer In Ireland (A Crown of Triads)

composed by Máistir Aodh Ó Siadhail

Sharing with us his entry for the Laurel Prize Display at Cudgel War 2025: Máistir Aodh delights us with a triad. As he describes on his blog, a “triad is a medieval Irish poetic form, with some resemblance to the Japanese haiku”. Please see his blog for more information.

Winter

1.1 Three colours of winter: the black of night, the grey of the sky, the white of frost.

1.2 Three scents of winter: the smoke of peat, the sharpness of snow, the pine bough.

1.3 Three tastes of winter: the roundness of porridge, the salt of meat, the pang of hunger.

2.1 Three feelings of winter: being lost in the night, being cold, finding the firelight in the valley

2.2 Three fears of winter: the cattle lost, the food not enough, the coming of the snow.

2.3 Three hopes of winter: the warmth of the bed, the turning at the solstice, the coming of spring

3.1 Three birds of winter: the shrieking gull, the clucking hen, the bright robin.

3.2 Three beasts of winter: the cow in calf, the sow in pig, the fox in thieving.

3.3 Three places of winter: the fireside, the cliffside, the grave.

Spring

1.1 Three colours of spring: the green of the new leaf, the yellow of the celandine, the blue of the clear sky.

1.2 Three scents of spring: the milk for the calf, the garlic in the woods, the bitter last of the ale.

1.3 Three tastes of spring: the first of the greens, the new eggs, the fresh leek.

2.1 Three feelings of spring: the relief of eating, the worry of calving, the rise in the blood.

2.2 Three fears of spring: that the calf will die, that the cow will die, that the corn will not grow.

2.3 Three hopes of spring: that the calf will live, that the cow will live, that the corn will sprout.

3.1 Three birds of spring: the corncrake in the field, the gannet on the rock, the swallow in the sky.

3.2 Three beasts of spring: the calf by its mother, the piglet by the sow, the hare in the meadow.

3.3 Three places of spring: the river bank, the sea shore, the top of the hill.

Autumn

1.1 Three colours of autumn: the red of the berry, the gold of the leaf, the grey of the sky.

1.2 Three scents of autumn: the smoke of the fire, the mushrooms in the woods, the blood of the slaughter.

1.3 Three tastes of autumn: the sweetness of honey, the sourness of the sloe, the fresh-made bread.

2.1 Three feelings of autumn: the fullness of the belly, the comfort of the harvest, the dreams of the dead.

2.2 Three fears of autumn: the storm before the harvest, the boat lost at sea, the son lost in battle.

2.3 Three hopes of autumn: the grain store filled full, the salmon to smoke, the warriors victorious

3.1 Three birds of autumn: the goose in the bog, the swallows gathering, the crow among the dead.

3.2 Three beasts of autumn: the fatted boar, the climbing squirrel, the barn cat.

3.3 Three places of autumn: the wheat field, the peat bog, the battlefield.

Something old from the archives

curated by Saskia de Quaasteniet

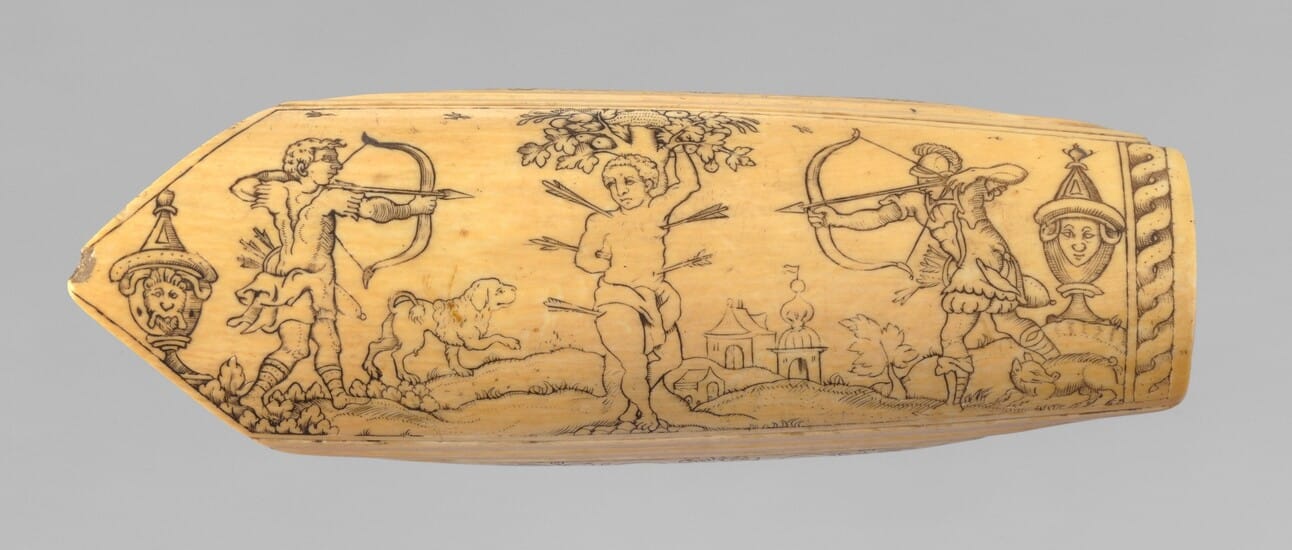

As we’re celebrating the first members of the Order of the Mark who have received their white bracers as a sign of their prowess, let us take a moment to examine some evidence of what archers would have used at the time.

Many of the archers within the society use a strip of sturdy leather wrapped around their forearm to prevent irritation or bruises from the string hitting the forearm and wrist. This is absolutely a wise precaution and something that archers from Ancient Egypt would agree with. In the collection of the Metropolitan Museum we find two examples (of small pieces of leather that wrap around the arm to secure them. Object 27.3.135 was taken from the Theban Tomb of the Theban Necropolis in a 1927 expedition, and object 23.2.76b which is believed to originate from Krokodilopolis (yes, your humble author did verify that name). Both objects were dated between 1500 and 2000 B.C., demonstrating the immense legacy of arm guards.

Advancing our time span by a meager 3000 years right to the 14th century, we see an illustration in the Geoffrey Luttrell Psalter (allegedly, the British Library online facsimile is no longer online to confirm this and therefore this author had to rely on Wikipedia) of some longbow men with an interesting accessory where one would expect the bracer to sit. Instead of covering a larger area for protection, these goodly hunters are sporting a rosette-like item that seems to stick out a little bit. As far as preventing the string from catching on one’s arm or clothing, that seems fairly counter-intuitive, so let us jump ahead in time and on to something more sensible. The Book of the Hunt, or rather, a Book of the Hunt (Ms. 27, Getty Museum) shows an archer with just a plain piece of black (presumably) leather. Interestingly, the archery has rolled up his outer sleeve, and put the bracer over his red shirt. This would imply the archer is using it to protect his arm, rather than keep his sleeve from getting in the way of his bow string. In yet another Book of the Hunt (BnF Français 1291) an archer is seen wearing a bracer in black (again presumably) leather but this time with a red strap.

Taking yet another step forward in time to the 16th century, there are some bracers that have survived the test of time. One notable surviving bracer is one found on the Newport Medieval Ship, a merchant’s vessel sailing between Lisbon and Bristol. The wrist guard, dated between 1446 and 1469, is made of leather and has intricate decorations, including roses and stamped text and shows some holes through the sides for closing the bracer.

Another decorated wrist guard was found on the warship Mary Rose. The Mary Rose was built in 1510 in Portsmouth, and made some remarkable journeys. However, on the 19th of July 1545 the Mary Rose was lost during the Battle of the Solent, and was only excavated in the late 20th century. The ship functioned as a time capsule, and still contained many objects that have been preserved particularly well. The bracer found on the ship was stamped with three different symbols, including an eagle or a griffin (though this author would also accept “owl” as a possible interpretation.

One of the more impressively decorated wrist guards this author has come across is a very early 16th century piece decorated with Tudor insignia and an inscription with traces of gilding. The curator comments that the skillful piece was likely an indication of high status of the wearer at the court of Henry VII. Looking at the pristine condition of the bracer, this author is inclined to agree that the piece was likely worn more for its artistry than its function.

All of the above braces seem to be made of dark brown or black leather, but the Order of the Mark’s regalia are two white bracers. Is there a precedent for that?

Yes, there is! The Metropolitan Museum has a spectacular bracer in their collection made of ivory, which is by nature almost white. Though in this day and age we shall opt not to use ivory for bracers, the surviving object is fairly impressive. The bracer itself is of Dutch origin dated to the late 16th century and shows an illustration of St. Sebastian, the patron saint of archers.

If you, dear reader, are still unconvinced by bracers, you can always opt not to wear them while you do archery. There are many illustrations of archers not wearing bracers, though as always the question remains as to how accurate illuminations really are as a facsimile of medieval life. You could opt to use a crossbow instead, eliminating the problem altogether, or perhaps even try drawing the bow with your feet. Although our model on the right doesn’t seem to be enjoying the experience that much. |  The Luttrell Psalter, British Library Add MS 42130 (medieval manuscript,1325-1340), f54r |

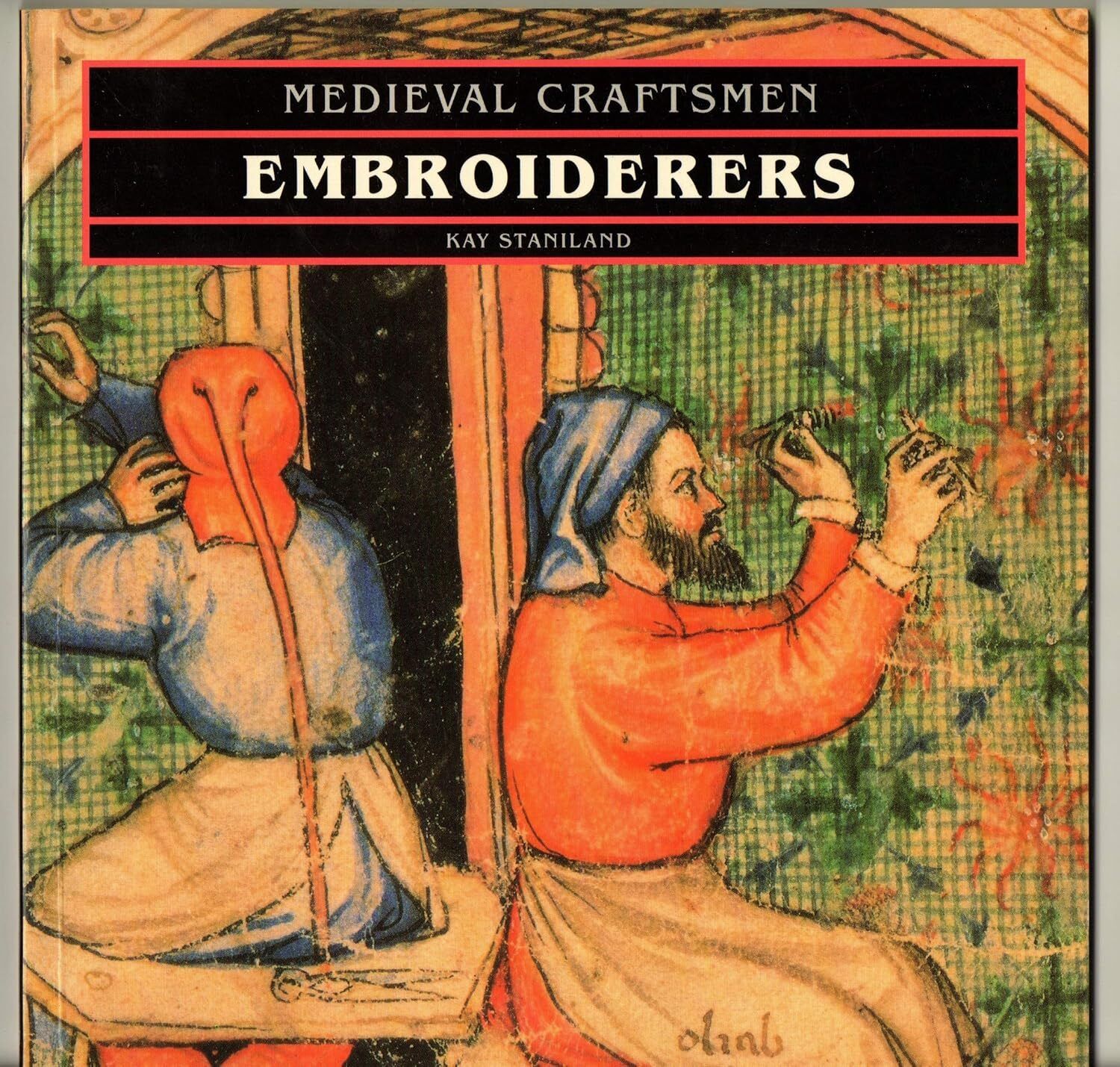

Book review: Medieval Craftsmen: Embroiderers - Kay Staniland

| Published: 1991 Publisher: British Museum Press Format: 72 pages, paperback ISBN: 0714120510 Language: English |

The scores:

Derpy animals: 7/10 with good representation from lions and one spectacular camel.

Silly headdresses: 6/10 some silliness, though most seem disappointingly sensible.

A&S inspiration points: 8/10 for a good amount of embroidered pieces, as well as illuminations and other visual evidence.

The contents:

The book immediately appeals with its cover of embroiderers at work, and that is a promise of the many illustrations inside the book. With the author being the Keeper of Costume and Textile at the Museum of London at the time of publication, one should expect no less than a good amount of visual evidence, in this author’s humble opinion.

The chapters are dedicated (mostly) to the different parts of the medieval embroiderer’s world. For example, there is a chapter on guilds, the designers of embroideries, the production of it and the techniques. All of these offer an interesting perspective on how the industry of embroidery functioned and how it can be a fairly isolated profession, while at the same time it is entirely dependent on other craftsmen or partners as well. For example in the chapter on design, the book explains how artists (painters) were often engaged by patrons to create patterns for pieces that would later be embroidered.

The chapter on production goes in depth into a variety of techniques, including brick stitch (on which Mistress Cat Weaver did a class at Strawberry Raid), counted thread, cutwork, needle painting, applique, quilting, couching and the enrichment of embroideries with precious materials. While not providing a literal tutorial for these techniques, the book shows enough examples to give some insight and sufficient inspiration, such as this beautiful badge of the Order of the Dragon. Very surprisingly, the book even provides some instructions on how to do common types of stitching mentioned throughout the book, like stem stitch and couching; even aspiring embroiderers with little experience can grab a needle and have a stab at the craft.

Overall it is quite a useful book for its size. With a solid-seeming further reading list, this book makes a nice entry point into the world of medieval embroidery and is definitely worth a glance if you ever come across it.

Did you enjoy this read? Consider submitting content for the next edition!

Please contact [email protected] for questions, feedback and content submissions. We welcome any ideas or suggestions 🙂

If you received this email but aren’t subscribed yet, click here to make sure you get the next edition!

Sigginstown castle flying the Drachenwald Flag - Photo by Paul Fitz